One week in Georgia (the ex-Soviet nation in the South Caucasus, not the American state famous for peaches), and I have to say: it’s cold, cold, cold. Especially after Delhi, where it was climbing past 35 degrees Celsius in the days leading up to my departure. The whole city is still in winter, just on the verge of spring; from the window in my first apartment I could see buds struggling to grow on the edges of trees. Along the boulevards and alleyways, a few white cherry trees have already bloomed and dropped their flowers on the street; mimosas, too, the kind Margarita carried in her arms when she met the Master, clump heady and yellow among the landscape.

It’s the first ex-Soviet Republic I’ve been to that isn’t Ukraine, and that isn’t speckled with family members. The city is beautiful, built in this sort of dip in the countryside, with a river running through it and hills along the sides, a gigantic statue of “The Mother of Georgia” on one of them, watching over it all. And it’s a fascinating mix of aggressive development and ex-Soviet ruin. Wandering in Dzveli Tbilisi, the Old Town, you find crumbling facades with nothing behind them, supported by possibly rotting poles; cats running around the streets, full in their winter coats (the cats in Delhi were all so sleek and short-haired, preparing for the summer, dozing in whatever patch of shadow they could find); men on street corners already red-cheeked from beer at 4 PM, cobblestone streets torn up and littered with rocks. And then! You turn another corner and there’s sleek English signage, Mercedes Benzes carting people around and blasting the most current American rap singles, Massimo Dutti and Burberry stores, coffee shops packed tight with hipsters. I walked all day my first day, getting lost on purpose, wandering and wandering.

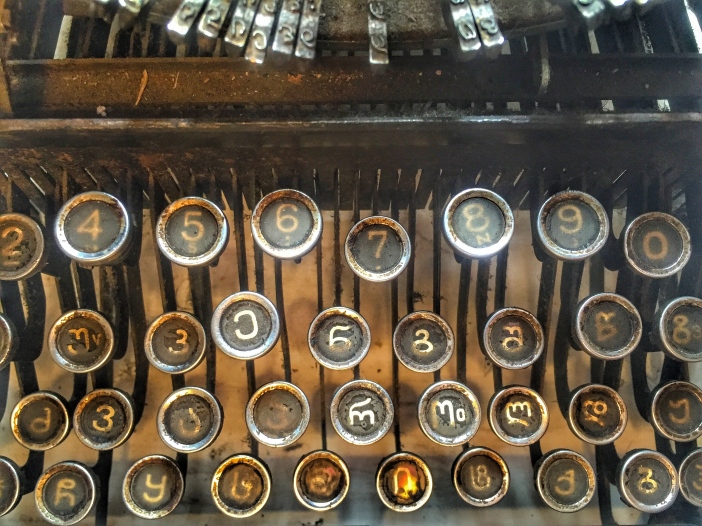

A few afternoons later I took myself to the Dry Bridge, Tbilisi’s main flea market. The ground is littered relics and tchotchkes for sale, from every era and of every type imaginable. Some people are professionals, equipped with a full arsenal of goods, arranged around a theme or specialty: vintage cameras, lenses, film; antique silverware and glassware; hunting knives. It’s history made kitsch: busts and magnets of Stalin and Lenin in every size you can imagine, Soviet-era medals of every shape and color, laminated pre-Revolution chervontsi and Soviet rubles.

Some aren’t professionals at all. Some are peddling whatever they could scrounge up in their house, anything at all that they imagine could interest a passing eye, tourist, nostalgic countryman: half-broken hair clips, mis-matched bowls, flaking enamel rings, handfuls of Soviet-era knickknacks. Their goods take up the space of a handkerchief.

Much of what is for sale reminds me of home. Of my grandmother’s house, if someone flipped the cabinets upside down and shook them out onto the pavement. Tbilisi feels like my childhood, too, flipped upside down and shaken, the pieces all mixed together: a crumbling metropolis, where I feel like a stranger, but constantly get mistaken for a native. Where I can speak with people in my two mother tongues, but not in theirs.